赛门铁克:对Adobe Flash和Reader0-day漏洞的分析

发布者:symantec 来源:http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/analysis-zero-day-exploit-adobe-flash-and-reader 发布时间:2010-06-09 14-58-36

6月8日,赛门铁克的高级病毒分析师Andrea Lelli在其官方技术博客上发表了文章,详细解析了最近爆发的Adobe Flash和Reader的Zero-day漏洞。

Last weekend, we warned our customers about a Zero-day exploit targeting Adobe Flash and Reader in the wild. The corresponding BID can be seen here. We have updated our antivirus definitions in order to detect this new threat as Trojan.Pidief.J, and we have done an analysis of this new exploit to understand how it works.

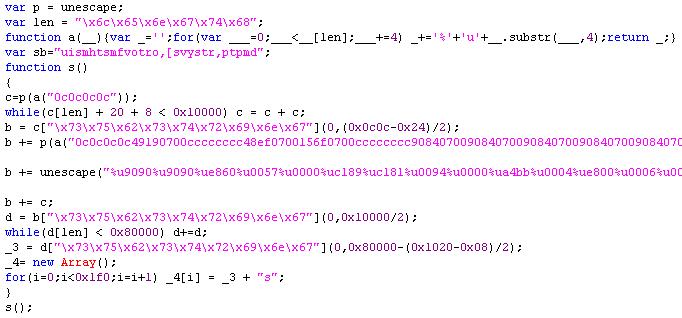

At first glance, the PDF document looks suspicious: it contains a Javascript object and a Flash application. The Javascript is clearly malicious, and has the typical form of heap-spraying code:

Image 1: Malicious Javascript code attempting to run heap spraying

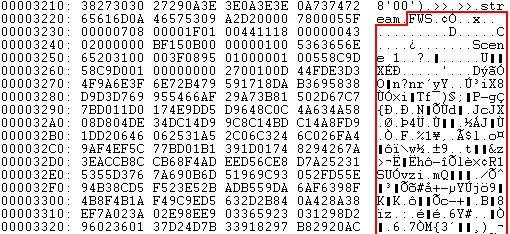

Image 2: A suspicious Flash object contained in the PDF document

Opening the PDF document with Adobe Reader causes the application to crash, which confirms our initial suspicion. A document used for an exploit should not crash, it should transfer control to the exploit code and run malicious actions from there. In this case, I am probably using a different version of the software for which the exploit was meant, or maybe the exploit is simply buggy or unreliable. Anyway, the crash occurs at this point in the code:

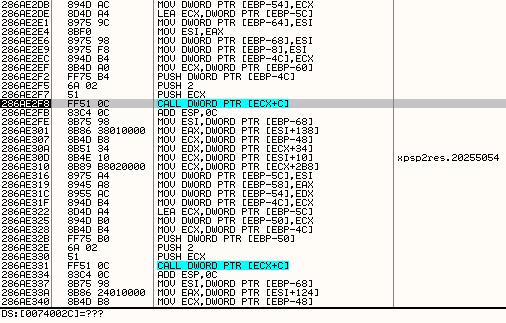

Image 4: Malicious shellcode to be executed upon successful exploitation

The shellcode is copied at different locations in memory by the Javascript heap-spray code. Notice all the '0c 0c 0c 0c' bytes written to memory, shown in Image 4; these are typically used in heap spraying. I manually ran the shellcode from its supposed entry point, and I found a decryption loop that decrypts part of the remaining shellcode plus some interesting strings, including a URL, shown in the red box in Image 4.

Where does this vulnerability originate from? As we can see, the Javascript code is only running a heap spray, but it’s not trying to exploit anything. So the exploit is likely to be in the Flash application itself. Let’s give it a closer look!

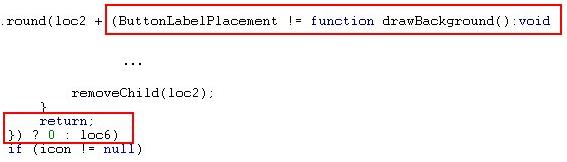

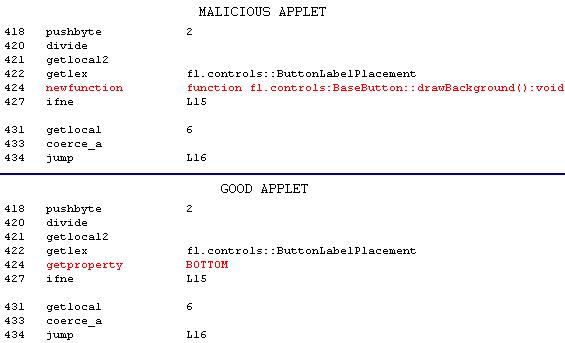

First of all, the Flash application looks like a legitimate application that was slightly modified in order to run the exploit. I started analyzing its ActionScript code, and I found some problems in one of the script modules. The tools I used to disassemble the script objects were giving strange results, like the two snippets of code in the following image:

Image 5: Incorrect code syntax

The syntax of the code is invalid; it seems the decompiler was confused and decompiled invalid bytes, so this is a good indication of where the problem could be. As I kept analyzing the Flash applet, I found several interesting strings inside it. Searching on the Internet brought me to a website that hosts the clean application, including its source code. I quickly downloaded the clean version of the application, and started comparing the bad Flash file with the clean one.

We know that something is wrong in this script and which particular module we have to look for in the binary data of the Flash application. Since I have the clean version, I extracted the ActionScript binary opcode bytes related to the buggy module that we see in Image 5, and I compared them:

Image 6: Binary opcodes reveal the malicious modification

One single instruction is responsible! The clean Flash application has a valid sequence of opcodes in the code module, seen in Image 5, because such opcodes were the translation from the ActionScript code that was legitimate. The attacker here did not alter the ActionScript code, he modified the compiled opcodes of the Flash virtual machine in order to insert an invalid opcode (“newfunction”) where it should not be allowed. As a result, the opcode interpreter gets confused when reading these opcodes, leading to an incorrect execution, which ends up as a memory-access violation.

This modification is very subtle, as the opcode is only two bytes long. When I restored it with the clean two bytes, the Flash application becomes legitimate. I also tried inserting the same “newfunction” opcode at different locations, and the Adobe software still crashes. Both Adobe Reader and Adobe Flash are vulnerable, which means that a malicious Flash application like this can be used both inside a PDF, like in the case of this analysis, or it can simply be embedded in a webpage.

Be sure to update your Adobe software regularly, and avoid opening documents or webpages from any untrusted or unknown source.